Find out about the pegword mnemonic

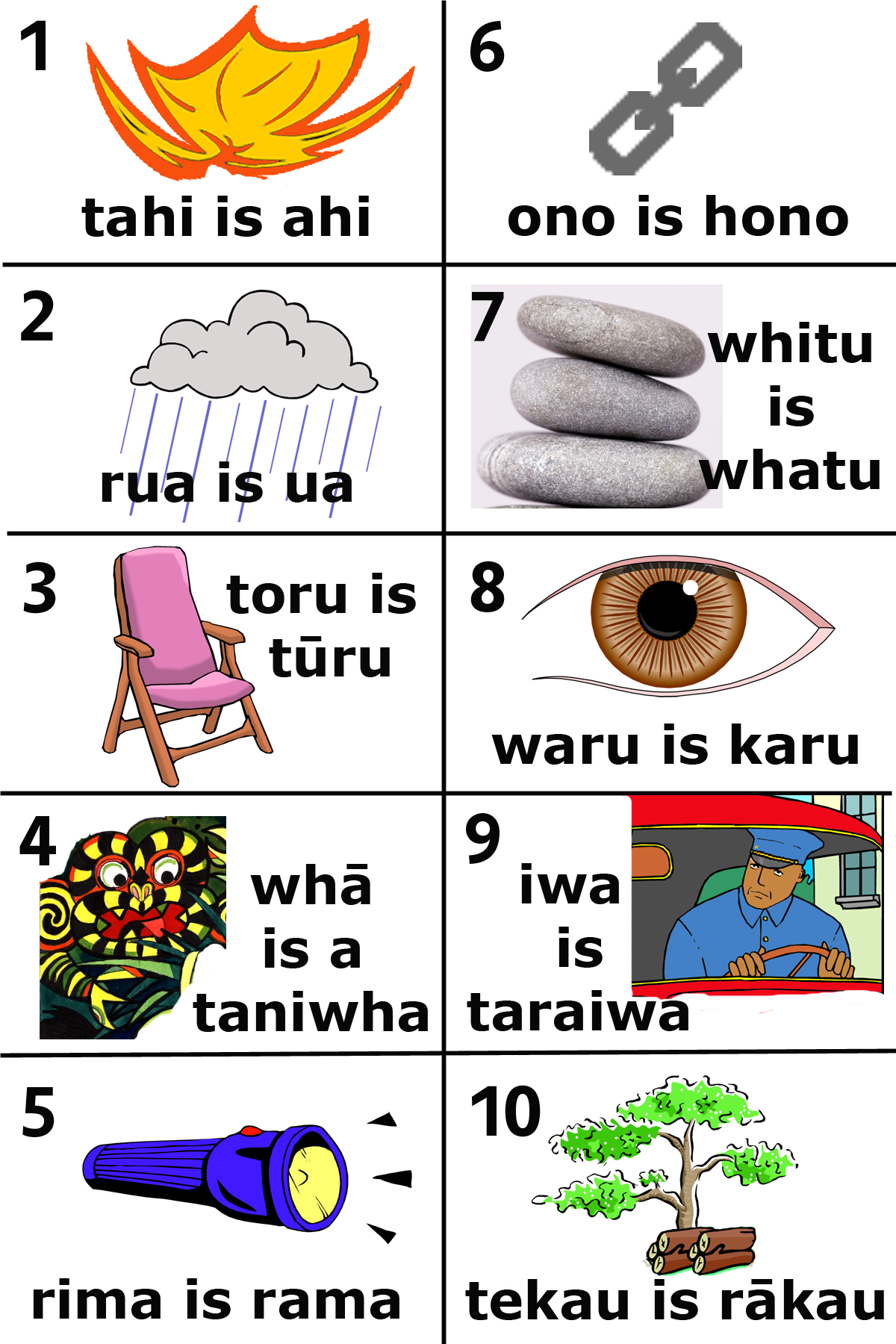

To celebrate Māori Language Week here in Aotearoa (New Zealand), I've put together a pegword set in te reo:

- tahi — ahi

- rua — ua

- toru — tūru

- whā — taniwha

- rima — rama

- ono — hono

- whitu — whatu

- waru — karu

- iwa — taraiwa

- tekau — rākau